FROM THE HOLLER TO THE SEA – Hurricane Helene Survivors Speak Out

–INTRODUCTION–

From the holler to the sea—a revolutionary battle cry coined by T & chels from Rednecks Rising—speaks to a sense of widespread solidarity amidst ongoing global polycrisis. From Palestine to the mountains of Western North Carolina, we recognize our struggles are interconnected as we face the present challenges of climate catastrophe, resource exploitation, imperialism & genocide.

In the following 18 chapters of poetry, prose, artwork & photography, survivors of Hurricane Helene recount their experiences and create a blueprint of survival for those who will be affected by catastrophe in the weeks, months, and years to come. Their words and images are as harrowing as they are inspiring—when everything we know washes away, we still have strength in community and the hope of building a brighter future. We still have our profound connection to the land and our shared desire to restore balance & harmony to our Earthly home.

The Scribes are proud to partner with Rednecks Rising to bring you this powerful collection of Appalachian survivor stories. Five months have gone by since disaster struck their mountain communities, but the work to rebuild continues. A number of the writers & artists featured below have included links to fundraisers and mutual aid efforts you can support with donations and volunteering. Please consider extending a helping hand in the ways that you can.

𖤣.𖥧.𖡼.⚘

Featuring the following poets:

Elisabeth Cox, Iris Delong, Bri Snyder, Kate Wargo, Zachary Harris, Ellie Varn, Kayleigh Dugger, Tamara L. Hanna, Beth Godbee, Lily James, Caitlin B., Cassius Guthrie, maybe, Sara Watson, A. Kelly, Michael Rainwater, Callen Clark, and chelsea wh.

–Table of Contents–

Chapter 1: Helene by Elisabeth Cox

Chapter 2: Haunted Mountains by Iris Delong

Chapter 3: Trickles & Chasms by Bri Snyder

Chapter 4: Inner Lands by Kate Wargo

Chapter 5: Underwater by Zachary Harris

Chapter 6: By the River by Ellie Varn

Chapter 7: Symbiotic Biotite by Kayleigh Dugger

Chapter 8: Grief by Tamara L. Hanna

Chapter 9: In Gratitude by Beth Godbee

Chapter 10: A Flood by Lily James

Chapter 11: Dust in the Air by Caitlin B.

Chapter 12: Wildfire by Cassius Guthrie

Chapter 13: Still Around by maybe

Chapter 14: To Survive by Sara Watson

Chapter 15: No Unruined Stone by A. Kelly

Chapter 16: Lost Futures by Michael Rainwater

Chapter 17: In These Ruins by Callen Clark

Chapter 18: Get Free by chelsea wh

FROM THE HOLLER

TO THE SEA

HELENE

she came and she went

dancing over us,

leaving a grave in her wake.

she was an unexpected visitor

just here a spell,

just long enough to destroy her host.

helene.

she left her mark on everything.

three months later you still see her signature everywhere.

helene.

her work remains apparent

from trees still down to houses demolished.

the creek bed forever changed,

in the shape of her name,

helene.

she came and she went, and life moves on.

cleaning up her mess,

the well needs to be shocked still,

limbs picked up,

chainsaws rip through the tree trunks she knocked over so carelessly.

helene.

the roof was fixed pretty quickly,

and we have gallons and gallons of water in the closet now.

just in case the faucets run dry again.

i’m one of the lucky ones.

thankful she didn’t punch me harder.

but she still grips my throat with survivors guilt,

the scars she left are permanent.

helene.

she came and she went and we stayed here.

danced over us,

leaving a grave in her wake.

helene.

More from Elisabeth Cox—

elisabeth is a queer & disabled artist from western NC. they make art for the sake of art, pouring their experiences and passion into everything they can manage to create. from collage art to poetry, they come at their projects with a sense of sass, compassion, regular passion, chaos, and quirks that blend into a uniquely human perspective. find more at bogbatart.com

APPALACHIA

Haunted mountains, foggy eyes

Banjos crying on Appalachia land

Frosted antlers tip toe through silk ferns

Woodland secrets slip through trees

Roots collide with dark green moss

Fae dance to notes carried by wind,

and soft spoken owls.

Haunted mountains, foggy eyes

Ever lasting river, where humans cannot

hide.

⚘

VIOLENCE OF HELENE

Life and death, isn’t it poetic

And during this flood, you break off

into me like branches that won’t save

the others

Hazed mountain ridges

Heart shatters in the shadows of the

toxic mud flowing in the street

Reality feels like hallucinations in a

nightmare

Storms making a valley of destruction

Remembering exactly how the river

looked, I can paint it on your skin by

memory.

More from Iris Delong—

I’m Iris, a two-time published poet in Asheville, NC. (JanusWords 2024 and Understory 2024).

The hurricane was an absolute devastation to our city and surrounding areas. I was a local vending and coffee business owner, and now I’m not.

I was denied assistance from every program for relief, and lost too much income to be able to continue services. I even lost my car, as I could not pay for it anymore after the hurricane.

Safe to say too many people have lost so much.

My 2 poems – one about the hurricane and one prior to the hurricane that expresses the unique feeling of being in Appalachia.

There’s so much trash in the trees

it almost resembles streamers.

As if the trees have been prepared

for a celebration

of death, of life, of destruction and

rubble, of renewal and community.

It’s somber, but it’s all the comforts of

home, it’s queer.

⚘

TO THE RAIN:

I need you, but you symbolize so much

more than umbrellas and rain jackets

now.

I’m uncertain of how to repair my relationship

to you, to the river, to the creeks, my

home.

In every way I can muster I will find joy

in you.

I will allow joy to make strong concoctions

in me, like plastic chemical spills

mixing and creating new molecules within

me, I will let it hurt.

The turbidity of the water in my toilet

mocks how foggy my brain is, how

disorienting, but they say the

sediment will settle one day.

I will wait till then and bless the rain

for helping clean up the mess it made.

⚘

The river has always shaped me,

slowly rounding out the harsh edges

this world breaks me into.

Now more than ever I feel it has

eroded so much of myself.

Not gently, not slowly.

No amount of packing dirt will

hide how changed I am.

Where trickles existed

chasms have opened.

Oh brother let’s go down

down to the river to

pray.

⚘

For a week I held my tears

afraid if they started falling

the banks wouldn’t be able

to contain my grief &

all the rivers might flood again.

With a candle and anger

I went to the place I call home,

the water’s edge,

there I mourned.

I said to the river:

“I don’t know how to forgive you,”

a blue heron flew up the calm brown river.

More from Bri Snyder—

My name is Bri Snyder (they/them), and I was born and raised in Appalachia. These poems speak to how my relationship with this land has changed as a result of Hurricane Helene. After leaving the church as a teenager I found spirituality in our local rivers and streams, they seemed more forgiving than the God I was raised with. This storm, however, reminded me that water is to be respected. I am working on not fearing it, not being angry with it, but accepting that it is capable of giving life and taking it.

a deconstruction of self

like a hurricane

tearing away at the land

your inner lands

its waters carve into the flesh

of the mountain

your body

the mountain

overwhelming you with its waters

your waters

so many tears

leaving behind barren land

inner land once teeming with life

your life

torn apart from within

the pain is unbearable and too much

to see

to take in

to digest

stop

stop

stop

and just when it feels like

you'll never emerge

never feel alive again

never create

or laugh

or dance

or feel love

or breathe deeply again

you do

you do

you do

Sculpture by Rebecca Habing.

More from Kate Wargo—

My name is Kate and I'm a survivor of Hurricane Helene residing in Fairview, NC. I am a local writer, Yoga Nidra facilitator, and founder of Gallery Tales – a creative writing and visual arts program for kids held in various art galleries of Western North Carolina.

My poem on the hurricane and resilience was further inspired by artwork from Rebecca Habing, a local tattooer, ceramicist, and painter, who worked on the piece pictured above during the daylight hours after the hurricane hit.

My people are underwater

A lady called

She wants to know something

My people are underwater

“What’s the Scoville rating for Chamoy sauce?”

Depends on the chili pepper used

My people are underwater

What did they say on the new Splendid Table?

I think they called it: Does This Taste Funny

My people are underwater

“I’m bored”

As he tried to swipe things from my desk

My people are underwater

700 National Guardsmen

Bombs on Lebanon, Beirut, u.s. postage

My people are underwater

Thoughts and prayers

Can I still make it to the Taylor show in Gatlinburg?

Dolly’s place?

My people are underwater

Toxic water

Flooded lungs of pine and sand

Blood of the Cherokee, so many others

Intermingled RDX, copolyester, George Eastman’s legacy washing up the graves

Filling my kitchen

Writing in the dark

My people are drowning

⚘

Silt and slag

Long Island of the Holston

Sacred to the Cherokee Nation

Unceded, ungiven

Its offering now

Nothing but waste

Covered up today

Refuse

In-house

Refusal to move

Drowned in hubris

The Norfolk just went by my door

Head in my hands

Neurotic, worrisome

Every trouble in the world

People I’ll never see

Or meet

But they meet me

Shrapnel and white phosphorous

Stamped with the price tag of my meager comfort

Maybe the train is heading north

Where a train derailed

An entire community

Poisoned for generations

Like the children born abroad

With Agent Orange in their bodies

That town’s name

Up in Ohio

A familiar ring

Maybe it’s heading east

Where mountain folks weathered a 1000-year flood

Entire towns

Washed away

1000 years is right

Just about every year now feels like it

History moving fast

The weather faster

The creek fastest

Nothing getting better

Death at home

Death abroad

Heavy metals washed through a school

Flotsam and poison detritus pillaged from the Earth’s depths

Heavy metals used to destroy a school

Several schools

Explosive minerals dredged from the depths

By a Man from the East

Norfolk chugs by

My little cat watches it go

First leaves of fall brush her nose

I can’t remember if I’ve fed her today

More from Zachary Harris—

My name is Zachary Harris, I penned these two poems in the immediate wake of Hurricane Helene. Looking back on them now, they read much more like a desperate attempt to process some pretty tough emotions at the time. I work at the Johnson City Public Library in Tennessee and, while I was volunteering in Elizabethton and my friends in Greene County were virtually unreachable, I penned these as I was struggling to come to terms with the schism of “normal" life and absolute disaster going on around Johnson City.

THE PACOLET RIVER

The Pacolet River is said to be named the “fast running horse”

I love the river, I live by her.

I live by her coursing waters the same way I live by the blood that flows through my veins.

She is the sound that endlessly fills my ears, she whispers and echoes of eons past.

She whispers to me and she murmurs to me in the night,

She fills my mind with dreams and washes my soul.

Her water is the water my garden thrives on,

The garden from which food my family gathers around the table to eat.

I worship her waters, her sand and silt, her flowered edges,

and carefully carved stone from a thousand years of water.

I played in her waters as a child,

joyfully admiring her sparkling gems and small creatures.

Her steep shaded banks covered in hemlocks,

dense forest concealing the dramatic water cascades.

Her many children,

birds and fish and countless salamanders.

The great blue heron who watches over the North Pacolet,

A messenger to always heed,

As the river’s eyes are within.

I knew to fear her as much as I loved her. I knew where she buried the dead and where her waters reached. She roared, she swelled with rage. She took away what I knew. She is my home, my protector, and she is who I fear most of all.

When the River Pacolet takes, she takes all she touches. She takes our homes, our land, our memories, our everything. She waters my garden, she devours and she destroys my garden. The river, my home, water of healing and destruction.

Melrose will never be the same, the graves of stolen lives are washed away too.

The old homeplace may still stand, spared because of some sacred reverence we held for this valley. Maybe it was the buckeyes we held onto and the horseshoe above the door that spared us from the worst.

It’s such a small community of fragile memories. Smaller than even Saluda, a delicate collection of quiet people living humble lives. The abandoned rails no longer sing, and now, the homes are empty shells. Oh Melrose, will you ever be the same?

Pacolet still runs, runs like a horse to the east. She whispers to me and comforts me. She loves me, but even after all this time her water is still red with clay, and I can only think of blood.

⚘

EXCERPT FROM MY JOURNAL: GETTING HOME AFTER EVACUATING

We drove around and under fallen trees and power lines until the road was impassable. We got out, climbed over the tree, and then kept walking around the bend. Then we saw the first mudslide, which completely covered the road with debris and mud that went up to your knees... we were still upstream of the water treatment plant. We kept going, with down trees everywhere, and passed the water treatment plant, which although a tree fell on it was relatively unscathed. The next row of houses though, was ripped apart. The small creek had become a river swallowing anything in its way, and that neat row of homes, used or unused, was totally trashed. A mudslide on the far side of the road made it nearly impassable. It just kept going like that, getting increasingly worse, until we saw where the entire mountainside had given way and nothing remained. The road was gone. A whole house was gone. The trees were stripped off the mountainside, and it was a bare cliff of stone and muddy clay going straight up for hundreds of feet. I was mortified. I was sure the house was gone then. The smell of propane gas hung in the air and the scampering over fallen trees, through mud, and around debris was starting to wear on Mom and Dad’s bodies and spirits. I was fearful at this point that someone would be trapped in their home, injured, or worse, and I was furious that the world was trying to stop me from going home, to my ever-beloved home. I grabbed two sticks and used them as stakes, and hauled myself up a steep, but undisturbed, bank on the other side of the gorge, upwards to an old logging road at a higher elevation away from the creek-now-river below that was making the route impossible to navigate. I scouted ahead and told Dad that I would signal to him with an acorn cap whistle, 1 was for attention, 2 was I’m coming back, 3 was I need help. I all but ran along the mountainside, unbothered by the normal discomforts because I was already wet, filthy, and hot, using saplings on the bank to steady me. I ran into two middle-aged men, one older than the other, who were looking out. They said they didn’t see anyone, but that their driveway was completely blocked, since they lived on the high ground, not low by the creek like the rest of us. I told Dad, and tried to keep pushing ahead, but I saw ahead of me what horrified me. Both banks on either side of the valley, streaking down with red clay... utter destruction below. No houses, no forest, just raging water.

⚘

PHEOBE

I see you everywhere

Your song reminds me that the mountains still love me.

On the old logging road home.

In the valley of rubble.

By the river's edge,

On the tracks on Main Street

By the lake of refuge

You are still here

You comfort my lost heart

You return me to my center

⚘

JOURNAL EXCERPT

I remember when I was little going into the attic and Mom asking me to gather up all the toys that I didn’t like or didn’t play with. She said we were sending them to Louisiana because the kids there had no toys to play with. It was after Hurricane Katrina. She told me the mountains protected us from hurricanes, but that in Louisiana they had no mountains to protect them, so the water took everything away. Now, 20 years later, the mountains could not protect us. We also lost everything. Now I just have to beg for help and pray we make it through it.

Photos by Helen Joy George @helenjoygeorge

More from Ellie Varn—

from Saluda, NC

GoFundMe:

https://www.gofundme.com/f/support-ellies-family-and-community-recovery

Any funds donated above are going to help us pay for a bridge to get back to our house.

SYMBIOTIC BIOTITE

These mountains, light filled,

even the mudslides glitter.

Will you hold my hand?

Take care of me? This is the

most beautiful place on Earth.

–Kayleigh Dugger

Photograph “No Politics” by Remy Cox, edited by Kayleigh Dugger.

More from Kayleigh Dugger—

Kayleigh Dugger (any pronouns) is a crow trapped inside a human body in WNC. She takes pop-tabs off the can, and inspiration from anything they've heard ever. To hear more noise, follow them on ig: @whale.calls

FUNDRAISERS TO SUPPORT:

–First United Methodist Church in Waynesville, NC

https://onrealm.org/fumcwaynesville/-/form/give/now

My roommates and I organized a volunteer carpool from Western Carolina University, and FUMC is where we spent most of our time, go give your love to them and the amazing people who organize there!

–Gamers Haunt in Asheville, NC

https://gamershaunt.com/

This is a Magic The Gathering store in Asheville that had a tree come through their roof during Helene. They were able to reopen their doors in November, but WNC small businesses still need all the love they can get! Charla and the folks at the Haunt are a second family to me, so if you like MTG, please think about supporting them!

When the sea came to the mountains

What was it like for you,

O Ancient One?

Were you as shocked as we were

When the ocean sat above you

And the developments below

Left you no good choices?

Was it painful when the winds

Ripped fistfuls of trees

From the roots of your scalp

In the darkness of that

confusing night?

When you couldn’t hold on

To your soft, boulder flesh any longer

Were you like the grandson

Clinging to grandma as long as

he could manage

Until the forceful waters stripped

us all from each other?

Did you look down into this valley

Adding your tears to the deluge

Not wanting to harm

All that you cherished in your

shadows?

Were you like the mother

Not one single cell in her body

Wanting to leave her girls on the roof

With all the trauma that would

certainly follow

Before letting go

Did you fiercely whisper

Her same last words: “I love you!”

⚘

My heart has needed to see a

different story than the violence

that the ravaged landscape still

tells us every day. What if even

the Mountain shares our grief?

⚘

SURVIVOR’S GUILT VS SURVIVORS’ GRIEF

Guilt implies something done or not done,

culpability, responsibility that therefore

requires accountability.

But you did not bring this storm.

You simply survived it.

We’d address guilt with judgment, sentencing, consequences, and amends.

And in a guilty system, if we can’t restore justice, we remain implicated and blamed.

Those eyes of comparison invite the unconscious in us to raise defenses,

produce justifications, and deflect the blame somewhere, anywhere else because

guilt implies choice. It implies someone had more control.

Guilt will spin us into furtive action to anesthetize our internal and external pain.

Guilt constricts and cuts us off from ourselves and each other. Guilt leaves no

room for us to have a place of belonging in this story, and that is the home we lose.

But in the daunting expanse of GRIEF there is room for everyone.

Everything matters if we can be brave enough to allow Grief to take us in her arms.

Grief invites us to let go of the shredded illusion altogether—that distracting

falsehood that keeps us from things bigger than control.

Guilt is a swirling eddy of shoulda, coulda, wouldas...the powerlessness and

shame of luck and privilege that was no more our choosing.

Guilt will silence our feelings, telling us they need to stay smaller than others

because we survived. But Grief takes our hand and leads us deeper through our

individual sorrow, and if we have the courage to let her do her work in us, she

leads us to our deepest shared human longings:

I wish this had been different...

I wish this never had to happen to anyone...

I wish death, destruction, and loss didn't happen to anyone...

I wish we always took better care of each other and the Land.

We lament the discomfort of our guilt, when in fact guilt may be easier, possibly

more comfortable, and certainly more convenient than the Grief whose powerful

force will bring even more of the change we ardently resist.

Grief will strip us of our certainty, poke holes in all our beliefs about fair and

blessed and deserving. She will take us down to the unrecognizable studs of our

very identity—questioned, unraveled, lost.

But she will not leave us there!

No, unlike guilt which is a dead end road to the washed away bridge to nowhere,

Grief extends promises if we partner with her on this new path.

She will give us new eyes of clarity: what really matters.

Time is precious.

Divisions are pointless.

We are more alike than we are different.

We are here to love and be loved.

If we are willing to release comparison’s separation, we can wade into the waters

that surround us all. Grief will tenderize our hearts and stretch our skin to hold so

much more compassion for ourselves, for others, for paradox and complexity and

questions that do not have answers.

She will transform us.

And if we dare to learn to grieve well and grieve with each other it could change

the world.

We will never get that from guilt.

So let us change the language that builds the isolating prisons of our hearts and

minds, and instead hold out a lantern for this dark, sacred journey of being

human together.

More from Tamara L. Hanna—

Tamara L. Hanna is a licensed clinical mental health counselor who has specialized in grief, loss, and change for over a decade. She is also a resident of Black Mountain on Blue Ridge Road and drives through Swannanoa every day. In both ways she felt the personal and collective devastation deeply along with the wrestling of “survivor's guilt" which compelled her to write a piece that was circulated over 700 times in the aftermath. She is committed to serving the community with rituals to help us heal our relationship to the land, cultivate joy, and to be neighbors united rather than divided in our long term recovery.

IN GRATITUDE

How do I thank the trees who protected?

Those who fell between bedroom and car

Those who didn’t crush the house

Those whose roots held strong

Those whose didn’t

Those who remain and those who’ve fallen

How do I thank the people who provided?

Those who responded first, after, and later

Those who brought food and drink

Those who cut trees and cleared roads

Those who said “I’m here” and “here!”

Those who showed up and those who couldn’t

How do I thank the organizers?

the communicators?

the caregivers?

the engineers?

the artists?

the arborists?

the educators?

the cooks?

the healers?

the responders?

the recipients?

the neighbors near and far?

I bow down,

body low,

humbled to the core,

and repeat:

thank you, thank you, thank you.

I pour out grief,

shaking and wailing,

and then find myself laughing, of all things.

I walk among trees,

hoping each step offers a gentle, nourishing touch.

I learn more how to receive with grace.

I text and call,

seeking connection and saying again:

thank you.

As life unfolds beyond my knowing,

As I happily unlearn the distance between us,

As I change into what I hope will be a more resourced, showing-up self,

I touch the earth with ever-deepening fortitude.

In gratitude.

Photo taken mid-day on Friday, September 27, when first venturing outside after the storm.

More from Beth Godbee—

Beth Godbee, Ph.D. is a public educator, writer, and former writing studies professor. She moved back to Southern Appalachia and newly to Asheville, North Carolina, just ten weeks before Helene. Join her for writing groups, retreats, workshops, or coaching through Heart-Head-Hands: Everyday Living for Justice.

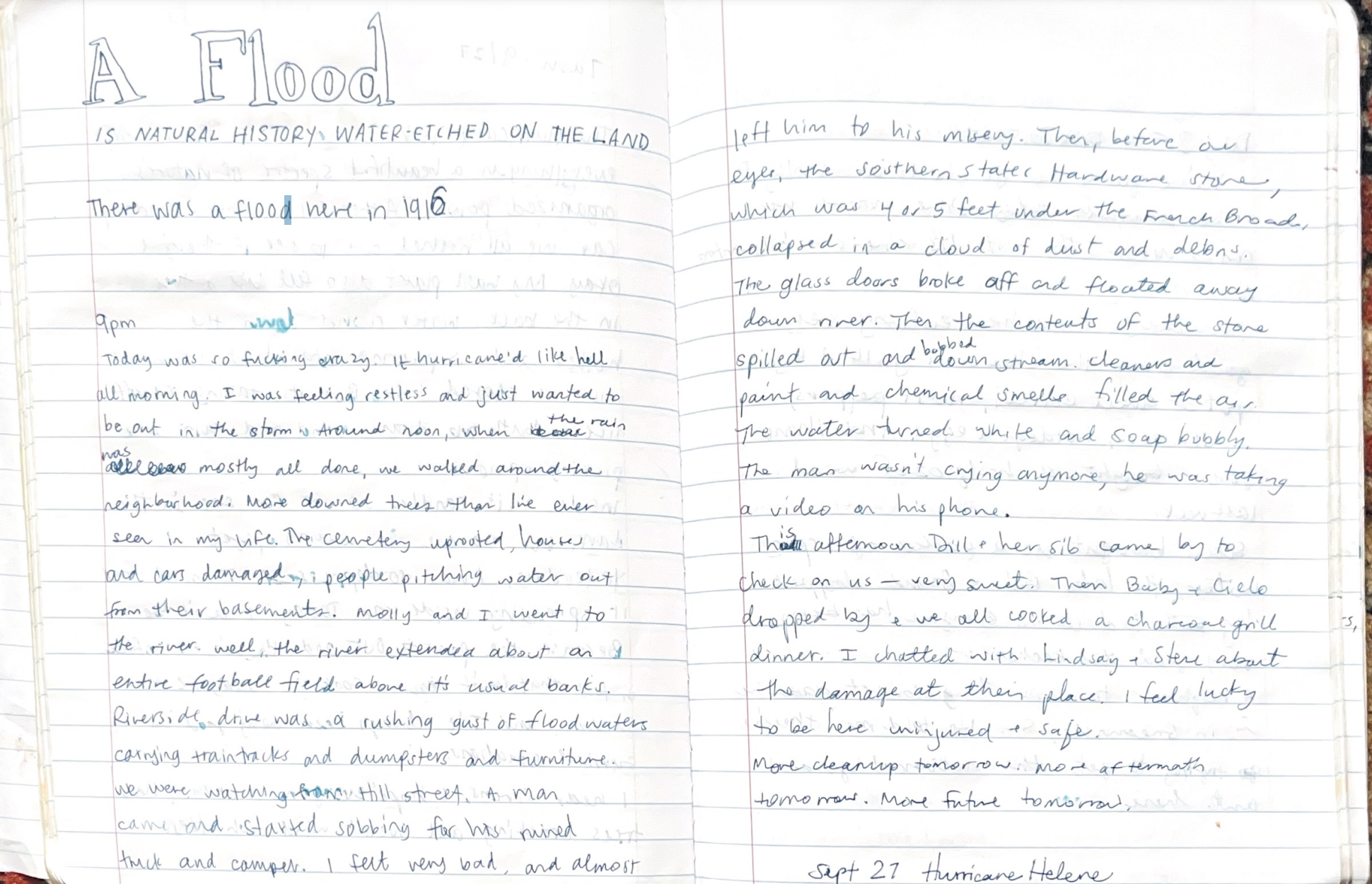

*Journal entry transcribed below.

A FLOOD

A flood is natural history water-etched on the land.

There was a flood here in 1916.

9pm.

Today was so fucking crazy. It hurricane’d like hell all morning. I was feeling restless and just wanted to be out in the storm. Around noon, when the rain was mostly all done, we walked around the neighborhood. More downed trees than I’ve ever seen in my life. The cemetery uprooted, houses and cars damaged, people pitching water out from their basements. Molly and I went to the river. Well, the river extended about an entire football field above its usual banks. Riverside Drive was a rushing gust of flood waters carrying train tracks and dumpsters and furniture. We were watching from Hill street. A man came and started sobbing for his ruined truck and camper. I felt very bad, and almost left him to his misery. Then, before our eyes, the Southern States Hardware Store, which was 4 or 5 feet under the French Broad, collapsed in a cloud of dust and debris. The glass doors broke off and floated away down river. Then the contents of the store spilled out and bobbed down stream. Cleaners and paint and chemical smells filled the air. The water turned white and soap bubbly. The man wasn’t crying anymore, he was taking a video on his phone. This afternoon, Dill & her sib came by to check on us – very sweet. Then Baby & Cielo dropped by & we all cooked a charcoal grill dinner. I chatted with Lindsay & Steve about the damage at their place. I feel lucky to be here uninjured & safe. More cleanup tomorrow. More aftermath tomorrow. More future tomorrow.

September 27 Hurricane Helene

*Journal entry transcribed below.

TUESDAY – DAY 6

I made it to Celo today. Asha & Carmella brought me & Oliver up there because they knew which areas in Yancey were impassable. Eventually, the landslides got so bad we had to abandon the car on Hwy 80 a little past Micaville and we walked the rest of the way to South Toe carrying shovels, chainsaws, and food. Houses were in piles and the road was completely gone in some areas. Nicole scooped us up at the Poplar Grove. It was noisy with helicopters and ATV’s. I saw no FEMA, no National Guard. Nobody but local people. We talked to everyone. I’d heard the farm was gone, but I didn’t expect it to be vanished. We worked on trying to salvage pieces of the greenhouse from the flooded field. It felt kind of absurd – in the face of complete devastation – to just pick a task to start with. But we did.

The mud made my skin itch badly. I thought the water might be cleaner up there, but this rash I have on the inside of my elbow has me wondering. Some lady gave Gaelen some deer meat which was fuckin delicious. It’s cool to see people taking care of each other. I found some random things – furniture & toys & tools – in the flood wreckage, and Nicole recognized some of it as her neighbors’. I’m back in Asheville now, fucking exhausted and fucking hungry. I ate instant grits that took over an hour to make. It’s hard to get water to boil on the charcoal grill.

When I was a kid, I used to fantasize about being in a natural disaster. I imagined a short, but intense, struggle for survival before I’d ultimately be air-lifted to safety or rescued. So far, I’ve only been rescued by my neighbors, who also could probably benefit from being saved. But I think all our adrenaline is gone.

Pictured above are journal entries from the author’s experiences of the storm from their home in the Stumptown community in Asheville and as a farmworker at Green Toe Ground Farm in the South Toe community in Yancey Co. Also pictured is the collection of notes left on their front door in the days after the storm when all phone and internet services were down. Lily says, “I've been keeping all the notes from that time (there are dozens) as a reminder of how surviving meant reaching for connection every chance we could, even when it was just a shred.”

The below photographs were taken in the aftermath of the storm. Lily says, “Due to the storm, my home was without electricity for 4 weeks, without clean water for 53 days. I work 3 jobs, all of which were either forced to close or were displaced due to flood devastation. We are still working on restoring hot water to our home, mitigating mold damage, and trying to figure out what the fuck we're supposed to do about the sinkhole that opened in the driveway.”

More from Lily James—

Lily James (they/she) is a musician, farmer, and nonprofit burnout who lives on occupied Cherokee land in so-called Asheville, North Carolina. They survived Hurricane Helene with their sister, housemate, a foster dog, an electric chainsaw, and with the help of the mutual aid networks who saved countless lives in WNC in 2024.

FUNDRAISERS TO SUPPORT:

–GoFundMe for Patty

https://www.gofundme.com/f/grandmothers-home-of-15-years-lost-to-fire?qid=824ecb1813714557d74c92d27a6a92dc

Patty is a rural elder in South Toe who lost everything she owns when the house she rented caught fire in January. Although the fire wasn't a direct result of the hurricane, she has been volunteering with flood cleanup, cooking meals and knitting mittens & hats for the community since Helene.

–Southside Farm

https://app.ribbon.giving/campaigns/camp_e8MP2D46PR62BbMj

Support Black food soverignty in Asheville. This farm has been fighting tooth and nail to stay open despite the city of Asheville Housing Authority trying to shut them down.

There’s something about the dust in the air

That tightens your throat and mutes the sun’s autumn glare.

Kind people come from far and near to comfort and to ease despair.

Others loot the rubble and bow to false profiteers

Who sow deceit and fear that tear through the soft flesh of hope.

And hope becomes just another word upon which we choke.

There’s something about the dust in the air

And neighborhoods flattened by nature’s indiscriminate warfare.

Kind people deliver water everywhere.

It is life but it is also death.

The water took our water, and out of everything lost, the irony was not.

It left us soaking and dirty and thirsty and grateful and distraught.

There’s something about the dust in the air

And the rhythm of sirens and choppers slicing through the silence of towns underwater.

Kind people drive around sharing bread and cookies and hot soup

While angry gun shots pierce the crisp mountain air

And the echoes rattle through my shivering bones as the hunger disappears.

The hypocrisy of humanity ringing in my ears.

There’s something about the dust in the air.

The grit in your teeth and smell of decay we all share.

Kind people send money and prayers

And trash bags full of used sweaters and shirts and underwear.

Desires to do good turn into a chaotic rush

Creating mountains of excess and waste – an instant relapse – an addiction to stuff.

There’s something about the dust in the air

And the millions of splintered trees and mud-choked roads to nowhere.

Kind people hike in with horses and mules and dogs

Bringing life and hugs and medicine to share

Because kind people are everywhere, but they’re tired and dangerously aware

That fear and hate wait at the doorstep for them to shrug and give up and not to care.

More from Caitlin B.—

Caitlin B. is an Asheville native, therapist, meadow-maker, tree-lover, and flower-grower.

“The places that grow you up are beautiful and complicated. Seeing them erased and the lives of friends broken, hurts. Digesting this pain and loss on a community-wide scale is a pain I don't even have access to yet.”

*Handwritten poetry art piece transcribed below.

WILDFIRE

Forced into a

great and

difficult

transformation

When a forest burns, the first to flee are often the last to return.

Birds take flight with startled cries, deer gallop and bound with tails

held high, frantic eyes searching for a scattered herd.

In the aftermath of a wildfire, when a life is burned and the

familiar is hollowed and rotted,

What remains of our former selves?

Do we find comfort in the nematodes and arachnids buried deep

within our being, working to fertilize our soul for healing?

Do we kiss the seeds brought out of dormancy, ready to begin anew?

Do we face the wind, bare and defenseless, knowing that what

stings our raw skin carries the beginnings of new microflora?

How do we shoulder such pain when the first to return to our forests

are not the birds or the deer, but the lichen?

How do we learn to hold the prairie grass in the same regard as the

catbird who sang to us every morning?

How can we trust that the supple oak yearling will one day grow

strong and sturdy again?

Aristotle claimed that “patience is bitter, but its fruit is sweet.” But

patience is only bitter if you make it so.

Thank the nematodes in your dermis, find the germinating endosperm and

kiss it, face the wind and know that the sting is the gift

of the new, the rebirth, of a restoration, and the deer will

return to lick the lichen off your cheeks, and the

catbird will come to wake you once again, and the hollowed

woods will be filled once more.

More from Cassius Guthrie—

Cassius Guthrie (he/it) is a 22-year-old Appalachian implant who found his roots galoshing in the rivers of the Pisgah National Forest in search of crawdads and mudpuppies. He graduated from the University of North Carolina Asheville in 2023 with a B.S. in Biology and minors in Neuroscience and Art and as an Undergraduate Research Scholar for his work with the American Chestnut Weevil. He weaves his knowledge of ecology and the natural history of Appalachia with both his visual and written artworks, painting a lyrical picture of the environment of an area and educating his audience on the nuances of various ecologic and biomolecular processes happening both around and within.

Artist Statement: “Written in the wake of tragedy, ‘Wildfire’ is inspired by a line brought to my attention through the work of ecopolitical activist and artist Liz Toohey-Wiese who erected the quote on a sign in protest of a wildfire burn used to clear land previously sanctioned for natural recreation in order to erect a business park. It was written in a residential treatment facility in the summer of '23. Then, two months before Hurricane Helene, I found the message of resilience essential in my journey through treatment and now, my journey through the wake of the hurricane. I share this piece with the hope that this mantra can offer comfort in a similar time of need, and that you remember the roots of the Appalachian deciduous forests run deeper than we often know.”

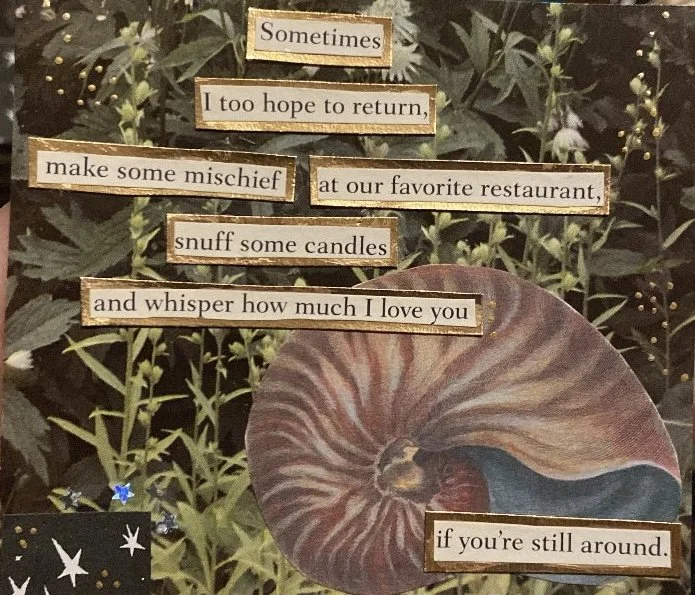

*Collage poem transcribed below.

Sometimes

I too hope to return,

make some mischief at our favorite restaurant,

snuff some candles

and whisper how much I love you

if you’re still around.

More from maybe—

My name is maybe, i make multimedia collages + recycled bone work. These mountains deeply inspire the feeling of safety, strength, + home for myself + thousands of others. The devastation of Helene has altered landscapes in the hills + our hearts, but no matter what we will keep telling our stories + loving as hard as we can.

Pansy Collective and Beloved are local groups to donate to + volunteer with.

TO SURVIVE A HURRICANE IN THE MOUNTAINS

A few things I’ve found to be fundamental:

First, keep your brain busy

In the beginning she will do this herself while simply trying to survive

Initially, you will not know how bad the storm really was

You’ll think sure, there are large trees down in your backyard

And the power has been out since you woke up that morning

But you will not be able to conceive that you could truly be without electricity and running water

For as long as they are predicting

When you venture out after the rain stops, in hopes of finding an easy meal

You will be appalled by drivers’ recklessness

Throughout town all the traffic lights will be powerless and gas pumps inoperable

You will be surprised to find that either no one knows to treat a down light as a four way stop,

Or they are all experiencing the terror of uncertainty,

Treating the road as every man for himself

You will be stopped short when following the underpass that borders the French Broad

To discover cars parked, doors open

An ancient tree lying toppled over, blocking even the idea of driving any further

People stand gawking over the guardrail while your boyfriend tries to turn their car around

You will look to see what everyone is amazed by

To find the river cresting higher than greenway paths

Higher than the bridges leading from West Asheville to the River Arts District

Higher than whole businesses that you once frequented

High up enough even to kiss the top of the riverbank where New Belguim’s brewery waits to see if she will be swept away too

Without phone signal or daily routines,

The pace of time will slow to a dismal cycle

You will do as much as you can during the day

To utilize the sun for all she’s worth

Then keep yourself entertained reading by what little candlelight will suffice

Fearful to leave flames in rooms unattended because with no water, there is no safety

Without screens glowing blue in your face, neck craned,

And extra weight from the stress of the day

Falling asleep soon after the sky darkens will become easy

You will keep track of the days that pass

Not by a calendar or tally marks on a wall

As if this were a cartoon on tv or prison movie,

But by seeing the dirt collecting under your nails

The nails which you will paint

Because you don’t want to be reminded of what you would usually be washing off

You’ll try to keep yourself convinced hand sanitizer is doing enough

If anything

The paint will chip to an amount that if you still lived with your mother

She would see your fingers and remind you to take better care of your appearance

The memory of which will drive you to take it off

Then one day, you will see the whites of your nails

At a length you would usually have cut a while ago

Because when they get that long, they are all you can think about;

You do so much with your hands

Time has gotten away from you

You hadn’t even noticed them growing

As you get further from your typical daily routine,

You will settle into the rhythm of One. Thing. At. A Time.

There will be entirely too much to worry about

And too little you will be able to control

So instead you will spend your morning with a single cup of coffee and a cigarette

Recalling your college days

When you allowed such dirty habits to be part of your routine

You will be glad you already were accustomed to making coffee with a French press

Boiling water on a camping stove to brew it with won’t feel much different

To try to conserve the little water you have

You won’t have the luxury of an entire pot to yourself

Splitting it with your boyfriend and their roommate,

Who graciously lets you stay with them

Since they actually planned and prepared,

Will have a romantic feel to this particular part of your experience

Until mid-morning hits

Then you’ll be wishing for that additional cup of caffeine

Your boyfriend might wonder if the pets will be affected by the fumes of the mini propane tank,

If the camping stove shouldn’t be restricted to use only outside?

But you will hear from a friend that theirs exploded

Causing a burn, the length of their thigh

No real explanation other than possibly being downwind when they lit it

Planning a trip the hour south,

A city without any familiar faces or comfortable places,

You need to stock up on canned food and propane tanks and copious amounts of bottled water

It will be the nearest place along the only way in or out of town

Landslides carried with them entire chunks of highway broken apart at the earth

Disrupting winding roads that could have previously led you to family or friends

Now trapping people that have lived among these mountains for generations

To wait for a helicopter evacuation

You will find the silence that settles slightly ominous,

Though initially unrecognized

As the chattering of chainsaws harmonize with searching sirens

The chorus of chaos amplifies and recedes;

A city unable to meet its peoples’ basic needs

And just as you notice the quiet of a town shut down

It will begin to crescendo again

At dusk sitting on the back steps at your boyfriend’s

You will begin to feel a restlessness that comes with unanswered questions

You will be grateful it is early fall

Chilly but not yet too cold

The bugs no longer bothersome

Your boyfriend will suppose they see more lights speckling distant downtown

To you, it will look just the same as the past few days

You will keep this doubt to yourself, not wanting to spoil small instances of hope

Doing dishes is something you will be able to stand for an hour

Maybe an hour and a half

But two would be too much time alone in your head

Hands working to somewhat sanitize this grime

Stuck to dishes untouched from back before the water went out

Piled in the sink and across counter tops,

Before paper plates and disposable cutlery had been acquired

On the back porch you will unfold your roommate’s long plastic table

Ghosts of pong partners past stand shoulder to shoulder with you

As you brave to plunge your hands in the water

Scarcely rationed and getting ever colder as time passes

This three tub system like an inefficient bar back station

Your standards for clean will become questionable

As you snail across the hour and a half time line

A buzzer will go off in your mind – you have met your limit

If you are careful, you can reuse the water that had cleaned your dishes

Or if you’re creative, you’ll think to collect the water which streams through the creek at the back of your neighborhood

With which you can fill the tank of your toilet

You’ll also learn that you must only fill the tank

After you need to flush

The habit of turning around to push the lever is one you can do half asleep

Or when your mind is not on this one thing at a time

You will be willing to drive from your boyfriend’s house back to your own

Since it is only 5 minutes on backroads

You will ferry yet another night’s worth of medicine and a change of clothes

Still having the mindset that all will soon be well

Without signal to use Spotify

You will scan the radio for what feels like the first time in ages

Hearing a Zach Brown Band song that throws you back in time

Reminding you of drives with your father

You will allow a couple tears to roll down your cheeks

A cleansing, but not quite a reprieve from the heat that has found a home at the back of your throat

Stifling what could lead to a real cry

It is much too early for any kind of breaking down

Or slipping of hope

You will allow yourself one split second

To be mad at your parents for not better preparing you

To better tough out a situation such as this

You will drag yourself back to reality knowing it is not their fault

They have lived entire lives with clean running water

And electricity at the effort of a switch

Why would they have thought to prepare you for weeks without either utility available?

The radio scan will prove fruitful as you discover the public radio station announcing multiple times to tune in for news

Getting back to your boyfriend’s

You will all huddle in whoever’s car has enough gas to idle for the hour broadcast

Listening to the latest at 4pm as city officials, heads of departments, and leaders of our town one after another will not really provide an update

The local bishop will claim a ‘biblical’ sized storm

Instructing that if you are a praying person, now would be the time to pray.

Meanwhile the answers to questions such as:

When will help arrive?

When will power be restored?

Where are you supposed to get potable water?

These questions will all be glossed over with some political jargon for “who knows”

You will be frustrated because shouldn’t they be the ones to know?

More from Sara Watson—

Sara Watson is a queer writer living in Asheville, North Carolina since 2021. Her writing typically consists of creative nonfiction pieces that connect feelings on community, family and nostalgia with imagery from a bad memory as well as the conscilience of human nature. She is most heavily influenced by Audre Lorde, Joan Didion and James Baldwin. Sara graduated with a degree in Screenwriting and Producing from Ohio University in 2019.

Sara recommends donating to Pansy Collective and Beloved Asheville, which are great local organizations. Also Homeward Bound WNC and Eblen Charities are community orgs that have helped people with rental and utility assistance where FEMA couldn’t.

NO UNRUINED STONE

The pickup hurtles around a bend in the winding road and I, along with a handful of volunteers, brace myself against the metal truck bed. Most are locals, seasoned in the line of toxic mud and flood debris, but some, like me, are new to the trade. I search for vestiges, dried stalks of summer joe pye and goldenrod along the roadside. Yellow sunlight filters through treetops, casting jaunty shadows on the valley; the ad-hoc settlements, rusty automobiles, and blighted gardens. And there, around the bend, a ruddy Main Street flanked by railroad line and river.

This part of Western North Carolina reminds me of the two-lane highways that twist and turn through West Virginia. My paternal grandparents live just north of East River Mountain, but the headstones of my ancestors lay ninety miles deeper into the arterial heart-blood of Appalachia, in Logan County.

Last July 4th I drove to Logan with my dad and grandma. We wound through extant settlements; sad towns forgotten since the decline of the regional coal industry. There isn’t enough flat ground in those mountain passages to hew so much as a graveyard; the graveyards looked as if a hard rain might wash the ancestors into town. We followed trout streams and train tracks. My dad leaned into the curves and my grandma had railed from the backseat, “You drive just like your daddy!” Logan, once a beaming hub of the coal trade, felt quiet; a row of vacancies lined Main Street and a Dollar General stood in place of the old general store.

Today, I’m cleaning out a tool cabinet at Every Angle, Inc. with another volunteer. The cabinet is chock full of toxic mud and we spend the better part of the day clearing out the drawers, washing the tools, and laying them in the sun to dry. The sun has elected to help us in this effort, and soon our hazmat suits are tied around our waists. Our task feels like an archeological excavation, like panning for gemstones, except the silt contains hazardous industrial solvents and instead of discovering your birthstone, you keep drawing socket wrenches. We work next to the river, bantering in echoes of shop talk: “I need a 12 mm socket to finish this set.” “Go fish!” Uncovering trinkets and knick knacks from layers of sediment, a machinist starts to take shape—you notice a pattern of existence, the quirks and oddities that outline a livelihood and a lifeforce, if only by contour.

In Logan, we had suppered at our Aunt Kay’s, passing peach cobbler and pots of coffee around the table while the elder generation recalled stories from the coal camp: hiking a picnic up to elephant foot rock, playing house in a boxcar and getting hauled clear to peach creek, family recipes born in the coal camp’s gardens. As hard as life was in the coal camp, everybody took care of everybody—a lesson my grandma repeated with each tale.

My dad and I walked out to the coal tipple, passing beheaded mountains and houses leadened by coal dust. I suppose it was the silent cry of the ancestors that beckoned us further up the gravel lane that follows the creek into the holler. I searched for remnants, shadows of that place in my grandma’s memory; for iron wash tubs and peeking chimney stacks, for creeping tomato vines and stray bean stalks among the weeds and brambles. But the coal company evicted its tenants and buried the town decades ago. The gravel lane narrowed, “overtaken by nature,” my dad nodded grimly. I searched for ghosts, but looking back it was us, their living heirs who haunted the coal camp.

The afternoon grows late by the time we finish piecing the tool cabinet back together. Before we leave, one of the volunteer coordinators wants us to see Bowman Hardware. We stand on the bare floor, looking across the empty hardware store. The flood swept away all of the store’s contents, except for an old wood burning stove standing stolidly in place. We marvel at the stove, which seems miraculous, like this old stove anchored the whole town against the floodwaters, and now cries from an older, more immutable way of life.

We walk across town and mingle with fellow volunteers over bowls of chili. We talk about how exceptional the mud was—remarkable properties, not your everyday, run-of-the-mill mud at all. A jar of apple butter passes around. I brush some caked mud off my forearm. “What are the symptoms of mud exposure?” I ask. “Dirt under your fingernails,” someone says wisely. A gruff man harrumps, “grit.” Others join in: “I got a sunburn and blisters,” “I had a sore back for a while,” “I get a profound sense of deja vu.” This last symptom arouses less laughter and more mumbles of agreement. Could exposure to a chemical from the upriver PVC plant inspire such recollection of lost time and place in us all? One fellow recalls a tale of adolescent Halloween haunts and others reminisce and tell old-time stories. I shudder, forgetting ghost stories are just stories, after all. My mind wanders back to West Virginia. My grandfather swore every day he was getting out of that ‘ol town of Logan, and he did—packed up his family and drove like hell on that winding country road. And still, he died last spring of COPD, choking on coal dust even after all the years.

Thinking of my grandfather’s exodus from Logan and my father’s flight another two-hundred miles from West Virginia, their unrest should carry me another five-hundred miles. But the farther I roam from the dirt that bore us, the more the distance maws me. If we don’t mourn properly, our children will bear our grief. I carry my ancestor’s bitterness and anger toward the industries that poisoned both land and people, as well as the stubborn, undying rootedness to place that led them to organize labor unions. Appalachia runs too thick in my blood—I won’t leave come hell or high water. If the dead won’t return to demand accounting, I must. I will mourn until the mountains heal, until the rivers run clean; long after the industries are driven out, I’ll still be haunting these hills.

I linger for a while as the evening’s curtain draws close and the pink sky of dusk fades into night. Plenty of folks are still communing under the string lights. Something magical is taking place as this community heals. I’m reminded of my grandma’s stories: “I’ll tell you, one thing I liked about growing up the coal camp. Everybody took care of everybody. The sprites and the Triplets and Glenn Davis next door to us—everybody took care of everybody.” I see resolve in the face of the man next to me. I see a woman with a walkie in her bib pocket organizing the community. I see locals boasting about Western North Carolina’s hardy stock. I see neighbors lending hands, clearing fallen trees, bringing food and water. I see businesses reopening and the crooked highway to Chimney Rock being rebuilt. In Marshall, I see a community bathe in muddy water and come out clean, strong, and assured—rooted in place.

More from A. Kelly—

A. Kelly hails from Marshall, NC.

HELENE

down in the water of the old gods,

i am learning to speak the language of destruction.

it is late in the day, my love.

it is late in the day and my love has

gone down in the water.

dark as an uncle's love.

dark as fishscales in dark water.

it is late in the day

and the laurel floats

together with indian pipe—

skimming the surface of our eyes.

it is late in the day and

my love is building

a new world from

mud and twisted baby blankets,

gathered from rooms without doors.

it is late in the day and

today, the cemetery is

a row of houses in a familiar place

with mouths wide open.

down in the water of the old gods

i am learning to speak the language of fish.

i am learning to say the names

of those still missing.

down in the water,

what was lost will not all be reborn—

but will still walk on our feet and speak

with our mouths.

it is late in the day but the words,

my love,

the words rise like foam to the surface of the river,

as we are clearing,

a path to our lost futures.

⚘

WOLF CREEK

Do you remember breaking ice along the river bank?

And the sounds of migration

sweeping over the fields like swans,

white against the sky, and the sky–

bleeding?

All of winter was a scapegoat.

Clouds passed dark as the new moon.

Dark as fish scales in dark water.

Do you remember how the water moved?

Her hips the color of cattails,

and in her movement—a wet, secret thing—

sleeping,

the way lovers sleep?

Held,

the way mothers hold?

Do you remember

names,

given so easily?

And quiet words for heartbroken things?

Do you remember our grandmother’s hands,

how they could scoop twilight

from the rose gold and honeyed edges of evening shadow?

How they could bind July's warmth in cotton

to leave draped over your winter shoulders?

And there are fish in the water that I cannot see.

And there are knives in my hands as they are growing old.

And you should know by now that all stories are forgotten,

if they stop being told.

More from Michael Rainwater—

Michael Rainwater is a poet and a carpenter living in the mountains of western North Carolina. His writing has appeared in Common Threads, and the anthology “I Thought I Heard a Cardinal Sing: Ohio's Appalachian Voices.” He also doesn't like writing about himself in third person.

Big mountains and wild rivers today and always.

THERE IS LIFE IN THESE RUINS

The storm brought destruction we hadn’t seen in generations.

Months later and I am still consumed with fear and hopelessness.

How might we recover from such disaster?

Yet, in my despair, I am forced to confront the beauty of life in its wake.

Clearing debris from an old riverbed, I see crickets in the sun, jumping amongst the shells of buildings.

The squirrels have made a playground where campsites once stood.

Bounties of mushrooms grow from fallen old-growth trees, mazes of mycelium consuming the rotting corpses of ancient behemoths.

Life is different, yet the same.

The whitetail deer must forge a new trail through this mutated landscape, yet nonetheless, it is forged.

My days are full of mourning, but still, hope finds its way.

Like the critters that we share this home with, we too carry on.

Like the whitetail, we forge a new path forward, little by little.

Each day is another road cleared.

Each day is another pile of debris gathered.

Each day is another neighbor fed.

I will tell you what I tell myself:

There is work to be done.

There is life in these ruins.

More from Callen Clark—

I moved from Boone to Hickory just a few weeks before the storm hit, and while I was lucky, so much of our community wasn't.

Since the storm, I've been dealing with a lot of feelings of survivors guilt and mourning, feelings that I'm still working through.

I was inspired to write this piece after Helene while doing some volunteer work in Hot Springs.

GET FREE

The tears of today will feed into rivers

That give life to lush forests of green

of a tomorrow,

Where we will pick olives from the trees.

A tomorrow where

The children will sing.

A tomorrow where freedom will ring.

The hearts cracking wide open today

Are fertile soil to plant the seeds

of a tomorrow,

Where Spring will bloom with solidarity.

A tomorrow where liberation will spread from the mountains to the sea.

A tomorrow where we can all be free.

“It is all just water under the bridge!”

Photo taken in January 2025, of a wall located inside the Hot Springs Spa & Resort, adorned with photos depicting historic floods in the area

More from chelsea wh—

You can find chelsea at Rednecks Rising Media on Instagram @rednecksrising, where she shares community resources for anarchist abolitionist Appalachians centering healing, storytelling, and organizing.

FROM THE HOLLER TO THE SEA, I’VE GOT YOU AND YOU’VE GOT ME.

𖤣.𖥧.𖡼.⚘

THANK YOU

TO ALL THE SURVIVORS

FOR SHARING YOUR STORIES,

WORDS & IMAGES.

WE HOPE YOU WILL CONTINUE

TO CREATE

AND DOCUMENT YOUR EXPERIENCES.

YOUR POETRY & PROSE

WILL LEAD US INTO A NEW WORLD.

TOGETHER.

With endless love & gratitude,